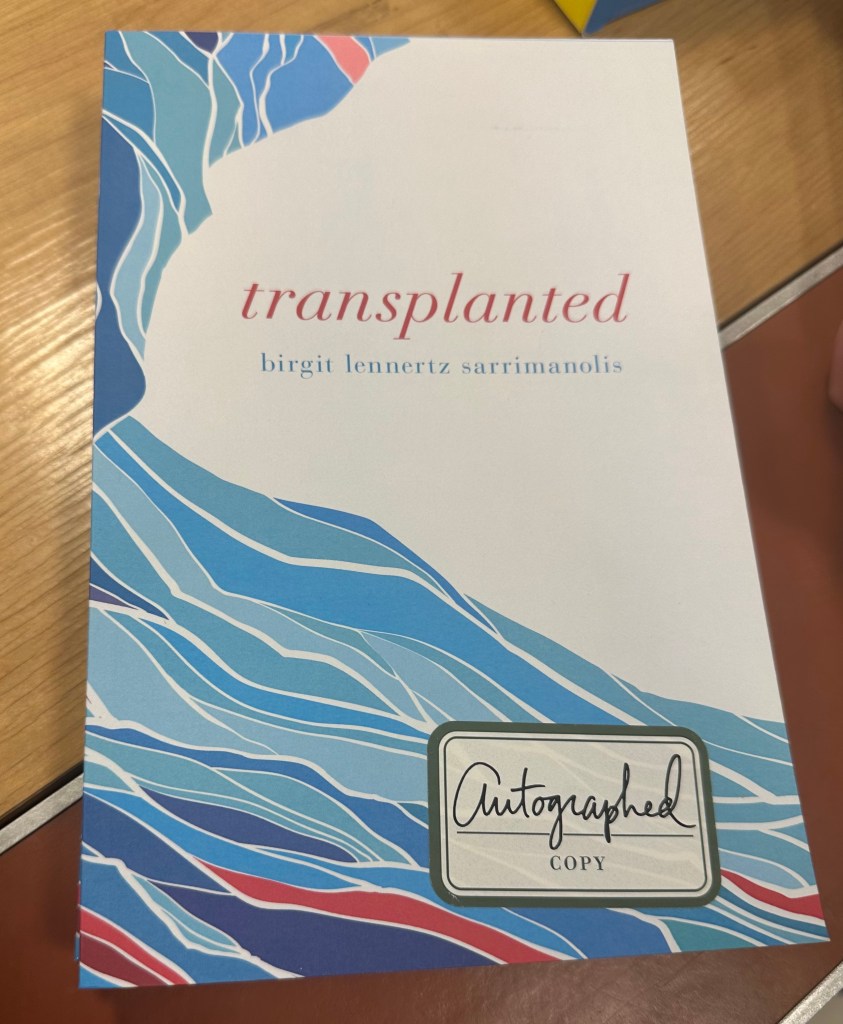

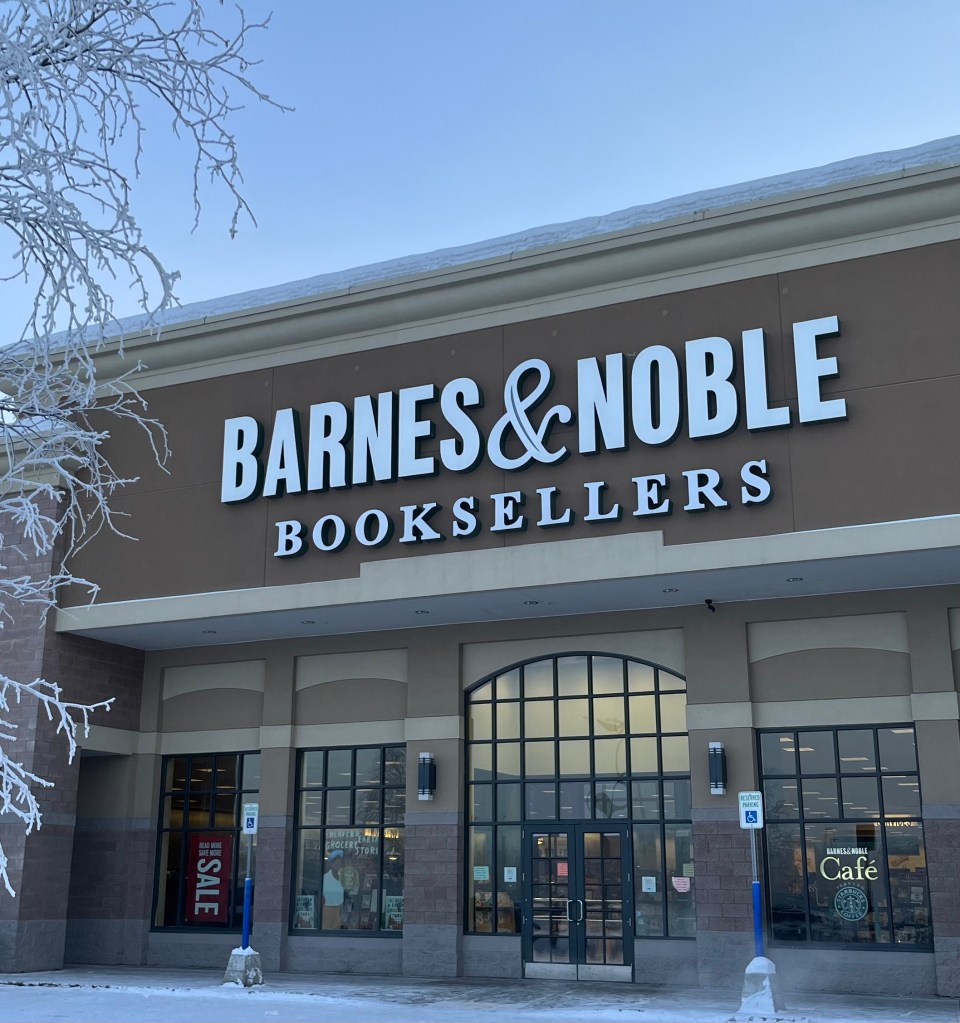

The thrill of finding my book on the shelves of Barnes and Noble Booksellers! Please stop by for a signed copy of “Transplanted” this Saturday, February 24, 2024 from noon to 6 pm, at the Fairbanks, Alaska store. I would love to see you there!

Writer

Another wonderful review by David James in the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner.

You can read the full review here:

Always up for an adventure, my friend Tara suggested a float down the Chena River. “If you can kayak in Alaska, you’ll be more than ready for any kayaking trip.”

I looked at her skeptically. Coming from a person who was keen to paddle between ice floes right up to glaciers in Alaska, I had my doubts. I had never even stepped foot into one of the shallow vessels. They looked like they could tip over any moment. Of course, she was suggesting an introductory paddle on the calm, inland waters of the Chena River, not the open sea at Prince William Sound. Plus, she was a trusted friend, one who would not urge me into harm’s way.

Still, I hesitated as she pulled the kayaks onto the muddy banks of the river. I eyed the preparations she was making, tossing me a life jacket, assembling paddles, securing her phone and car keys into a drybag.

“There’s a current,” I mumbled, looking out over the river at the slow drift of the water.

“What current?” she answered with a laugh. “Water does move, you know.”

Next to us, a group of more experienced paddlers were pulling their kayaks to the river’s edge. I hoped that they would deftly climb in and paddle away before they had to witness me loading myself inelegantly into my wobbling kayak. No such luck. Even their dog, wearing a lifejacket, seemed to grin at me as he jumped onto the front of one of the kayaks.

“First time,” I told them, humiliated, as they suppressed amused smiles.

Tara was not letting that stop us though. With a few words of instruction, she pushed me “off the deep end.” Thankfully, I knew that the Chena River was notoriously shallow. Even if I did capsize, I could trust my relatively decent swimming skills to get me back to shore. At first, all I did was swivel against my moorings and clumsily splashed water into my kayak. Immediately my behind was wet from sitting in a puddle. Is this why Tara suggested quick dry shorts?

Finally, we were off. Tara took the lead. I paddled frantically to keep close behind her. The river, swollen and murky, flowed lazily. It was early on a Sunday morning and there were few people on the river. Tara gave me some pointers along the way. Stay clear of “drifters,” random tree trunks that floated in the river and could surface to submerge a kayak. If a motorboat came my way, I should turn my kayak perpendicular to the wake so I could crest the wave without wildly rocking about. I broke out into a sweat and kept my eyes peeled for logs and boats.

After a while, I started to relax. Shifting, I had not realized how tense I was. I repositioned myself into what I hoped looked like a more languid pose and took in the scenery. I had lived in Fairbanks many years but had never seen the town from the perspective of the river that flowed through it. Boat houses, decorated with moose antlers, stood on the river’s edge. At times, the decks of neighborhood homes looked right over the river. More often the wilderness encroached onto its banks. We spotted a bald eagle perched high on a bare branch. A beaver had built his dam close to the shore. Fireweed blossomed on grassy embankments and willows wavered in the breeze. We floated by a huge sternwheeler with a paddlewheel, feeling miniscule alongside it.

I started to enjoy the current that propelled me forward. My only purpose this morning was to drift on the water and to see what the river presented to me beyond each bend. My first experience in a kayak might not have taken me to the edge of great glaciers, but it had given me a new glimpse of a landscape that I had started taking for granted.

On a Sunday afternoon after the first significant snowfall in Fairbanks, the landscape is blanketed smooth and white. The sunlight slants sideways, casting the spruces into a golden glow, a pristine world.

I try to animate my family. “Let’s go for a ski!”

They glance up at me from the couch and armchair where they recline, books in hand. Even though it is noon, they lounge, Helen in pajamas, Nick still unshaven.

“I don’t have any ski pants,” is Helen’s excuse.

“I want to finish the article I’m reading,” Nick comments.

I tell them I would assemble what we need for the excursion. I would find appropriate clothing, apply wax to the cross-country skis, gather poles into the trunk of the car. We are so lucky to live in Alaska, I tell them, where snowfall and skiing are always guaranteed. Even the US National Ski Team takes advantage of this, traveling to Alaska early, where they can begin their training much earlier than anywhere in the lower 48 states. They grunt back at me before they finally concede.

Of course, given the fact that we have not used the equipment since last winter, our preparations take some time. Helen grumbles that the ski pants she borrows from me are too big. Nick’s second pair, which I borrow, in turn, from him, are equally large on me. After we pull tight the drawstrings at our waists, we both look like balloons.

“Never mind,” I tell my fashion-conscious teenager. “There will only be moose out there to see us!”

Nick, when we arrive at the trails, realizes he has left his hat in the garage at home. I produce a bright baby-blue headband from the compartment in the car, which I hand him with grin. He looks at me in dismay but pulls it over his ears anyway.

Finally, even though not exactly trend setting in attire, we are off. Helen chooses the wider trail to skate ski. Nick and I follow each other along a narrower, parallel track which is perfect for classical skiing. Just as I try to tell myself that skiing is like bike riding, once learned. forever engrained, I turn to see Helen, arms flailing, lose her balance. She lands gracefully. I, however, head turned, chuckling, run smack into Nick. He had been plowing ahead steadily, like a tractor in first gear, but had chosen that precise moment to slow down in front of me. I land in the deep snow, from which I try to extract myself, skis crossed, poles jutting. I heave myself back up, dignity bruised, much less elegant in manner.

When we collectively find our ski legs again, the loop trail beckons. The skis hiss as they glide over the packed snow. We lengthen our stride on the gradual decline and feel as though we are flying. We call to each other, laughing, soon drenched in sweat. The air is crisp and invigorating. Who would have thought that moving forward across snow covered terrain purely by the power of our own locomotion could be fun.

Afterwards, we joke about each other. My “clomping” whenever the skis slid out behind me. Nick’s steadfast expression as though he were taking on the next 50 km freestyle race. Helen’s exaggerated panting whenever the slightest uphill presented itself, complaining that, unlike her father and me, it was not her intention to lose ten pounds before the upcoming Thanksgiving holiday.

We may have been the Flintstone Family on their first ski excursion of the season, but later, rubbing our sore muscles, we all felt there is hope for us yet.

Not many miles north of Fairbanks, the edge of the Alaskan frontier town gives way to an open expanse of wilderness. At its furthest reach, just beyond its fringes, one still comes across Fox, originally the site of a mining camp, a small settlement on the banks of Fox Creek. It consists of a collection of homes, a general store/gas station, and a spring that provides potable water, claimed by locals to be the best water source in the interior. It can be driven through in the blink of an eye. Somewhat unexpectantly, it houses several well acclaimed eateries – the Howling Dog Saloon, the Silver Gulch Brewery, the Turtle Club – popular with Fairbanksans and locals alike. Beyond these, however, the road twists off into a vast, mostly uninhabitated hinterland.

It is that emptiness of space that draws Nick and me to drive on. The temperature has, for the first time this year, dropped below zero. It is a Sunday afternoon excursion, spurred on by a little time on our hands and a desire for deep vistas. The last snowfall has left the north facing hills frosted in white. Spruces and birch trees line the road in different shades of grey. The road has crusted over with ice and crunches beneath our snow tires.

We come to the Hilltop Truck Stop, famous, we heard, for its homemade pies. We stop and park next to three trailer-tractors, enormous trucks, idling for now, until their drivers commence the fifteen-hour drive up the North Slope Haul Road, as they call it. Inside, the truck stop resembles most in Alaska: a counter selling chocolate covered raisins and beef jerky, Alaskan souvenirs, a flyer advertising laundry and shower facilities at Haystack Mountain. Wooden tables and chairs with red plastic seats accommodate a handful of customers, sandwiches and coffee mugs before them. Behind a vitrine, the pies: Strawberry-Rhubarb, Coconut, Apple, Banana, Fatman. Nick asks for a piece of each, to take home.

The door opens, letting in a truck driver and a gust of frosty air. He approaches the diner counter, smiles at the woman behind it. Acquainted, they fall into conversation. He looks tired, long journey behind him, after delivering supplies to oil field workers in Prudhoe Bay, on the Arctic coast.

I pause to think of it for a moment. We had not planned a lengthy drive today, but still considered packing into the trunk of our car extra jackets, boots, flashlights, mittens. What precautions would he have had to take, to embark on a drive that would take him the length of one of the most remote and isolated highways in the world. A journey that would take him some four hundred miles north, with no gas stations, restaurants, rest stops, hotels or cell phone reception. Only a gravel road winding north, potholed, heaved by extreme freezing and thawing, through unpopulated treeless alpine tundra, across the Arctic Circle, up and over Atigun Pass in the Brooks Range. He had probably encountered snowdrifts, or a blizzard, as he drove on, white-knuckled, gripping the steering wheel of his rig. He would squint beyond the windshield wipers, paralleling the trans-Alaska oil pipeline alongside, his only companion for hours. He would think about reaching Coldfoot, a tiny settlement midpoint, and be reminded of the fact that it got its name, when travelers, approaching the oncoming winter, got “cold feet” and turned back around. Should he be encouraged by the notion that his destination was named Deadhorse?

Yet he covers the distance, over and over, for reasons of his own. For a paycheck, most likely. Or, perhaps, to drive, unencumbered, into a world without edges. To cross the wide Yukon River and to think of its bearing as a major trail river of the north. To see tors of granite, jutting rock formations caused by weather erosion over years, on an alpine tundra. To encounter a herd of caribou as they slowly make their way across the road. To find oneself on a line that traces the Arctic circle, where the sun stays above the horizon for a day on the summer solstice, bathing its surroundings in light. Or to return to a truck stop, just shy of home, where the smile of a woman behind the counter tells him it was worth the journey.