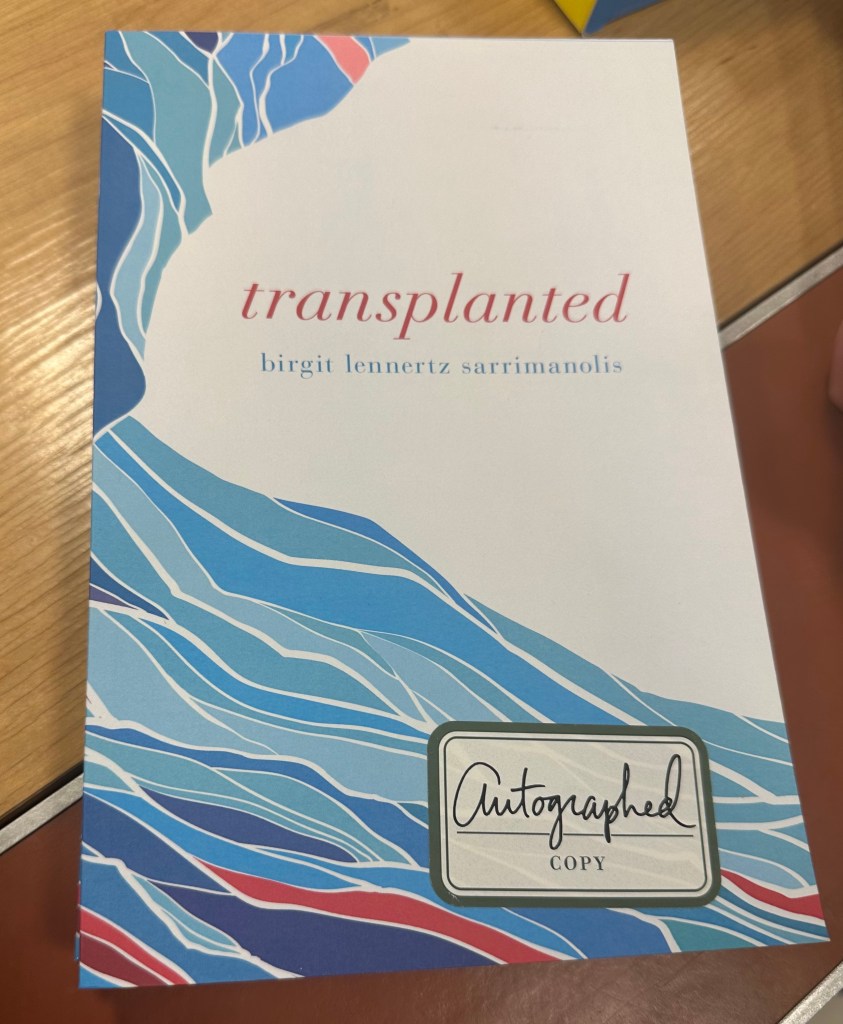

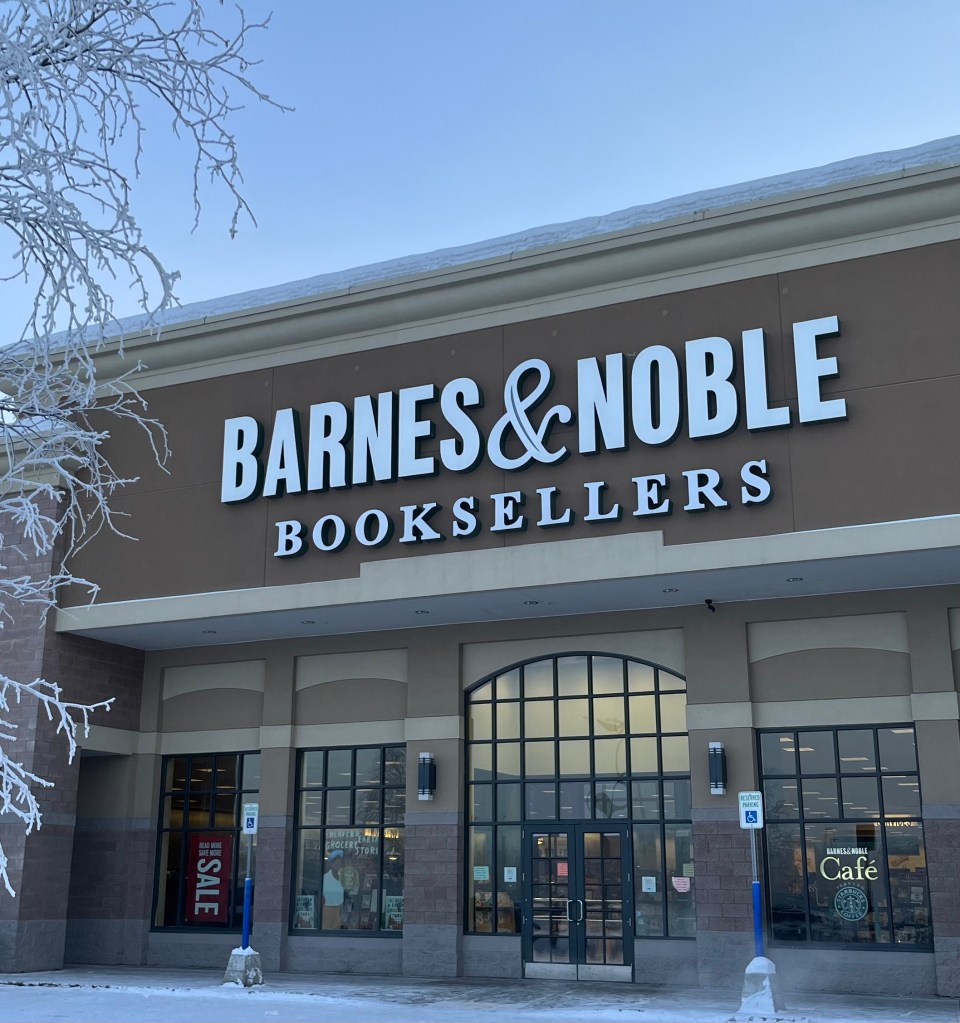

The thrill of finding my book on the shelves of Barnes and Noble Booksellers! Please stop by for a signed copy of “Transplanted” this Saturday, February 24, 2024 from noon to 6 pm, at the Fairbanks, Alaska store. I would love to see you there!

Writer

Another wonderful review by David James in the Fairbanks Daily News-Miner.

You can read the full review here:

“Transplanted” was reviewed by Nancy Lord, former Alaska Writer Laureate, for the Anchorage Daily News.

Please follow the link to read the review:

In September, after the kids returned to college and the summer frenzy slowed, a colleague of Nick’s offered to cover his medical practice. We jumped at the chance. In all our years in Alaska we had never had such a great opportunity. The landscape beckoned. The trees and tundra had turned ochre and yellow and red. The air was crisp. We embarked on a month-long adventure of camping in Alaska. Open-ended time in our own beautiful state. We packed our camper with supplies and followed the best weather. Just the two of us. And Jack, the dog.

Denali National Park was dramatic in its transition of colors. At that higher altitude, the nights were getting dark again after the long summer of midnight sun. It was the end of the tourist season. The shops and eateries at the entrance to the park were being shuttered for the winter ahead. The campground near Riley Creek was sparsely populated. Invigorated by the prospect of having the park mostly to ourselves, we hiked the Savage River trail, following the glacially fed, silty water along its watershed. Around us, mountains rose in sharp contours. We kept a look-out for Denali, the highest peak in North America, but it had concealed itself in its own weather system. Instead, we spotted a grizzly bear feeding on blueberries in the tundra. How fortunate to have been afforded a glimpse of him on his own land!

We headed further south, skirting Anchorage. We drove along Turnagain Arm, a waterway north of the Cook Inlet named such when the 18th century British explorer James Cook was forced to “turn again” at its end, not finding the fabled Northwest Passage he was seeking. Just the drive was worth the destination. Ragged, heavily glaciated mountains were mirrored in the water. When we crossed over onto the Kenai peninsula the slopes of the mountains were covered in scrubby vegetation that had turned purple and green and grey, a colorful brocade tapestry below bare peaks. We passed hiking trailheads and blue-green fishing creeks and biking paths. No wonder the Kenai is often called the playground of Anchorage. Glorious in autumn colors, we had a difficult time deciding which direction to steer into.

We settled into a camping routine, staying as long as we wanted at any given spot. We had neither agenda nor schedule. Our days were structured only by our own whims. We went for long walks with the dog, exploring our surroundings. We made bean soup one day. Chicken and rice the next. In the evenings we lit a campfire to thwart the chill of the evenings.

A couple of weeks into our outdoor undertaking, it started raining. The drizzle continued for days and the camper began to feel cramped. We had to physically rearrange ourselves to be able to coexist amenably in the small space. Jack the dog decided to forsake his pillow on the floor and make our bed his perch. Nick and I, armed with piles of books, alternated between the camper’s dinette table and the small couch. We read about historic Russian Orthodox churches in the towns of Ninilchik and Kenai. We learned that the enormous Harding Ice Field covers more than a thousand square miles, is hundreds of feet thick, and feeds more than thirty-five glaciers in the chiseled Kenai Mountains. We discovered that different species of salmon choose different types of rivers for spawning: Chinook lay eggs in fast-moving rivers while pink and chum salmon spawn in coastal streams. When we took a break from reading, we quibbled about whether the gray and black tank sensors gave correct readings and debated whether the propane tank would last to heat the camper all night. We drew sticks as to whose turn it was to walk the dog in the drizzle.

After fourteen days of “dry camping,” I started to question the wisdom of embarking on our extended enterprise. I missed the comfort of a flush toilet and a real shower. My coiffure, by now, could at best be described as “camping hair.” Being disconnected and unplugged from the world, at first idyllic, was becoming old. I wanted wifi, cell phone reception and Facebook posts. And a take-away pizza.

Then I remembered my “escape hatch.” I had bought an airplane ticket and packed a carry-on bag of normal city clothes, just in case. I brightened. Leaving Nick and Jack to fend for themselves, I flew to Seattle to attend the Pacific Northwest Writers Conference. The pretext, of course, was to attend writing workshops, mingle with other writers and pitch book ideas. The bonus was luxuriating for a few days in a hotel room with running water and relishing meals in restaurants. I returned north fortified and ready for the next two weeks of camping. Nick and Jack had fared well in my absence. The only thing I had (thankfully) missed was a black bear that wandered into the campground one night.

For our next venue, Nick had cleverly booked us a campsite with electric, water and sewer hookups. We parked our rig high on a bluff overlooking Kachemak Bay, just outside of Homer. The view of peaks and glaciers across the glittering bay was stunning. We explored the small town and its spit, a long strip of land that extended far into the bay. Home to artists, fisherpeople and outdoor enthusiasts, the town had a slow-paced feel to it. There were seafood restaurants, shops and art galleries. Outfitters advertised halibut charters, sea kayaking, bear viewing and boat tours to see whales and orcas. To our delight, there were a multitude of food trucks parked all over town. Now, instead of arguing about how to best light the propane cooker, we could decide whether we wanted crab rolls from “Sirens Seafood”, halibut tacos from “A Bus called Sue,” or a deluxe pizza from “Fat Olives.” We spent heavenly days walking along the spit and Bishop’s Beach where Jack played in the incoming waves. The only reason we finally left Homer was because the campground was closing for the season.

Next was Seward on Resurrection Bay. The last of the cruise ships sailed that night, aglow in the dark bay, as it set its course south. The harbor town, typically bustling with tourists in the summer, was settling down for winter. Many of the restaurants had closed for the season. At our campground the camp sites were empty and the picnic tables put away. The only other resident besides us was a bald eagle in his nest high above us. One day we hiked to the Exit Glacier in the Kenai Fjords National Park. We had seen it once before, twenty years ago, and I had photographed our children standing in front of its blue-grey mass of ice. Seeing the glacier from a distance, we were astonished to see how much it had receded, leaving behind a scoured, rocky landscape. Perhaps a little saddened at the sight of its retreat, we reflected on our years in Alaska. When had time overtaken us so?

After a month of camping, we were ready to drive north again to our house in Fairbanks. To break up the long drive, we stopped at Kesugi Ken for one final night. The campground, situated on a higher slope of the Kesugi Ridge, was closed but we parked at a day-use area where we built a campfire in a shelter and sipped wine in the gloaming. Across the valley, as though we needed any more rewards, Denali revealed itself to us in all its glory, its snow-covered peak white and soft in the evening light. Alaska has been good to us. We sat for a long time, humbled by the expanse of rivers and mountains before us, and quietly offered our gratitude in return.